Antony Gormley’s solo exhibition is at the Royal Academy until 3rd December. Tickets here.

Our bodies and the spaces that sustain us – where we live, where our food comes from, where our waste goes – are becoming harder to ignore. As the climate changes, as borders continue to be redrawn, as people around the world agitate for progress, living in the 21st century means being forced to re-negotiate how we inhabit a space and how we treat our environment. How are we changed by our surroundings? What will it mean for us as individuals when our environment changes, irreversibly? How do we live with ourselves?

For Antony Gormley, all these questions can be answered by looking at our own bodies. Whether they go Gormley’s lead people transform spaces: whether it’s a beach in Liverpool or a hill overlooking Newcastle, a space is impossible to see the same way once Gormley’s left his mark. In Slabworks (2019), the first room of the RA’s ‘Antony Gormley’ exhibition, fourteen blocky steel sculptures are draped around the room. At first the Slabworks are vaguely Spartan things, machine-sawed blocks of metal; notice heads, feet, a crooked arm or a bent neck and the slabworks reveal their human forms. They are no longer things in a space but people in a room. It’s a kind of full-body pareidolia; recognise the person and the space starts to make sense. Understanding our bodies is the first step to understanding the world.

Anthony Gormley is so famous that apparently his exhibitions don’t need names. I suppose this is a retrospective – exhibiting works from across his career – this is a show that tries to take on some of Gormley’s biggest and most general themes. Bodies are the central topic, and there’s a distinct emphasis on bringing the viewer to interact with the art as directly as possible. There are sculptures to step over and walk under, to duck past and crawl through; one of them even smells. You can even take a selfie without getting a filthy look.

Gormley is interested in whether the different ways that we take up space change how we live and how we relate to our bodies. In the courtyard outside there is a tiny iron baby, a cast based on Gormley’s six-year old daughter that was made in 1999. It’s barely a quarter the size of the paving slab it rests on and it’s quite difficult to get a good look at, there’s so many people crowded around it. Two more installations – Clearing VII (2019) and Cave (2011) – are so massive that they require contortion and squeezing-past to be properly experienced. Gormley says he likes sculpture because the audience is part of the art – the space where the art is and where we the art-lovers are is one and the same. One of Gormley’s strengths is his ability to make his audience consider the different ways that we expect art to be presented and how we think we’re supposed to act when we’re around it.

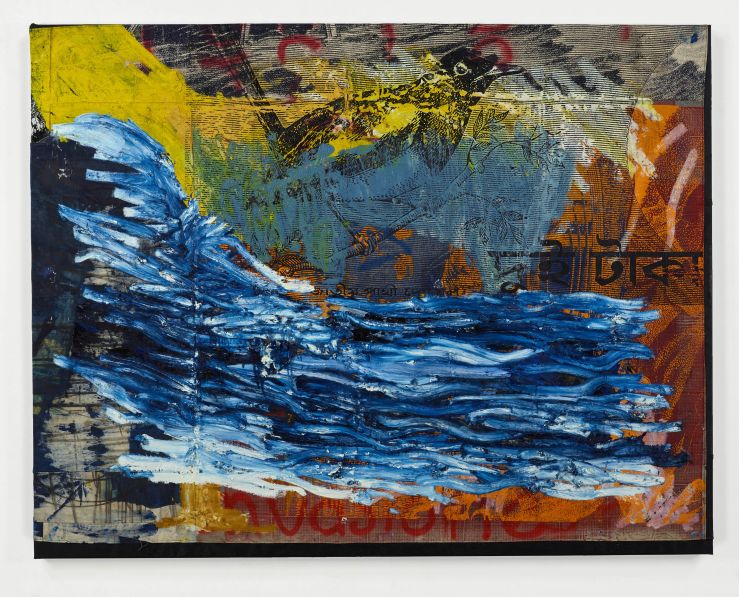

Other pieces aim to capture fleeting moments, exploring the contrast between the experience of seeing something beautiful, which is normally over quite quickly, and sculptures as things which can last for centuries. One Apple, a series of 53 lead casings that stretches across the gallery, shows each stage of an apple’s life from blossom to rot. Each casing contains the remains of the apple inside the lead. In ordinary time, an apple rots after a few weeks; the artist’s intervention freezes the apple in time and edifies a single moment. The wall drawing Exercise Between Blood and Earth is a chalk outline of something like a tree’s rings, and each time it is exhibited Gormley re-draws the outline and preserves another moment of energy and motion. These are works that look at the traces our bodies leave behind and the marks that we make.

It’s significant that most of Gormley’s art responding to ideas of time and preservation dates from the Cold War, when the threat of nuclear obliteration was a daily fear. It would only take four minutes or so for an H-bomb to wipe out most of life in Britain and Ireland, about as long as it’d take to sketch the concentric circles of a tree. But that chaotic instant, like all other instants, would be recorded for centuries in the tree’s rings. The Cold War may well have inspired Gormley to make these works back in the 1980s but, with the knowledge that every plastic bottle I’ve ever used will remain on Earth longer than I will, Exercise in Blood and Earth still holds the power to disturb.

Gormley’s sketches on paper and notebook studies are on display, adding a useful context to Gormley’s process and thinking over the years. I’ve always found Gormley’s sculptures to be slightly unmoored, unrelated to any obvious themes or politics that I could suss out. Of course, not knowing where the metal people have come from or why they’re here is part of the mystique of Gormley’s sculptures. The difference between a space and a place is how you look at it. A space is generally empty (the sea, the wild, outer space) whereas a place is a specific space filled with things (a house, a country, a political rally). And yet while Gormley’s sculptures undoubtedly transform the spaces they enter, I often feel they don’t say very much.

I do like Antony Gormley’s work, and there is of course no rule that says an artist should be tied to something loud and political. With Concrete Works (1990-93), what look like blank concrete blocks are revealed (by the programme) to be hollow, with the contorted shapes of human beings kneeling or praying trapped inside the stone. Notice the similarity with Slabworks? These blocks are the minimum space that a human being could occupy. You can’t help feeling that Concrete Works might mean something if, say, Gormley were responding to political violence, or religious persecution – instances where this kind of violence is very real.

On the other hand, it’s the fundamental unexplanability that gives Gormley’s work its bite. Because Gormley’s sculptures are just weird. They stand, staring out to sea, and we’ve got no clue what they’re thinking about. It’s the absence of meaning, familiarity, and simple explanations that gives them their magnetic pull. With lead men standing among the crowd, on the walls and hanging from the ceiling, it’s hard not to be awed by the eeriness of Gormley’s best work.

Besides, Gormley is basically a personal artist. Artworks like Matrix III (2019) are all about how we as individuals exist in space. This is a house, Matrix III says; this is where you’ll want to spend most of your life, if you can afford one of these. I overheard someone beside me in the gallery say that she was ‘mesmerised’ by the lines. Revealing the surreal elements of everyday things can’t fail to impress.

The logical conclusion of all this thought about how we live and how we make our mark on places is the final installation, Host (2019). Gormley has filled an entire gallery space with mud and seawater, making the white-walled, 18th century room look like Shoeburyness at tide-turning. It smells, faintly. Unlike Matrix III, or the solid casings of apples and people, this is a formless, undefined artwork. The formerly safe and specific place “the RA” is now a smelly, hazardous space “the sea” – a nasty inversion that’s familiar to anyone who’s ever had their house flood. The outside is inside, and there it is again – that sense of how strange the world can easily become. Only Anthony Gormley can give you this. The RA wouldn’t let anyone else.

Picture Credits:

- All images except Exercise between Blood and Earth were taken from the RA’s Exhibition page, here.

- Exercise between Blood and Earth is © Antony Gormley, and I sourced the image from this Tumblr blog. I assume the image copyright lies with Antony Gormley or the RA, but if not it’s the property of berndwuersching.

Please contact me for any copyright concerns.

%20BeowulfSheehan-detail.jpg)