I started my end of year review last year by calling 2019 an annus horribilis.

What a melon!

There is no need to rake over how bloody awful the pandemic has been. The other day someone on Twitter said: “The worst thing about writers is that they think they’re the first person to experience everything they experience”, and I don’t have anything new to say about the year we’ve all lived through. I’m lucky enough to have not gotten ill or to have been in work that’s exposed me to risk; as for most other people, 2020 has just been really exhausting. Let’s hope 2021 is more invigorating – that there are more chances to do things, to see people, to make changes. Now – the reading.

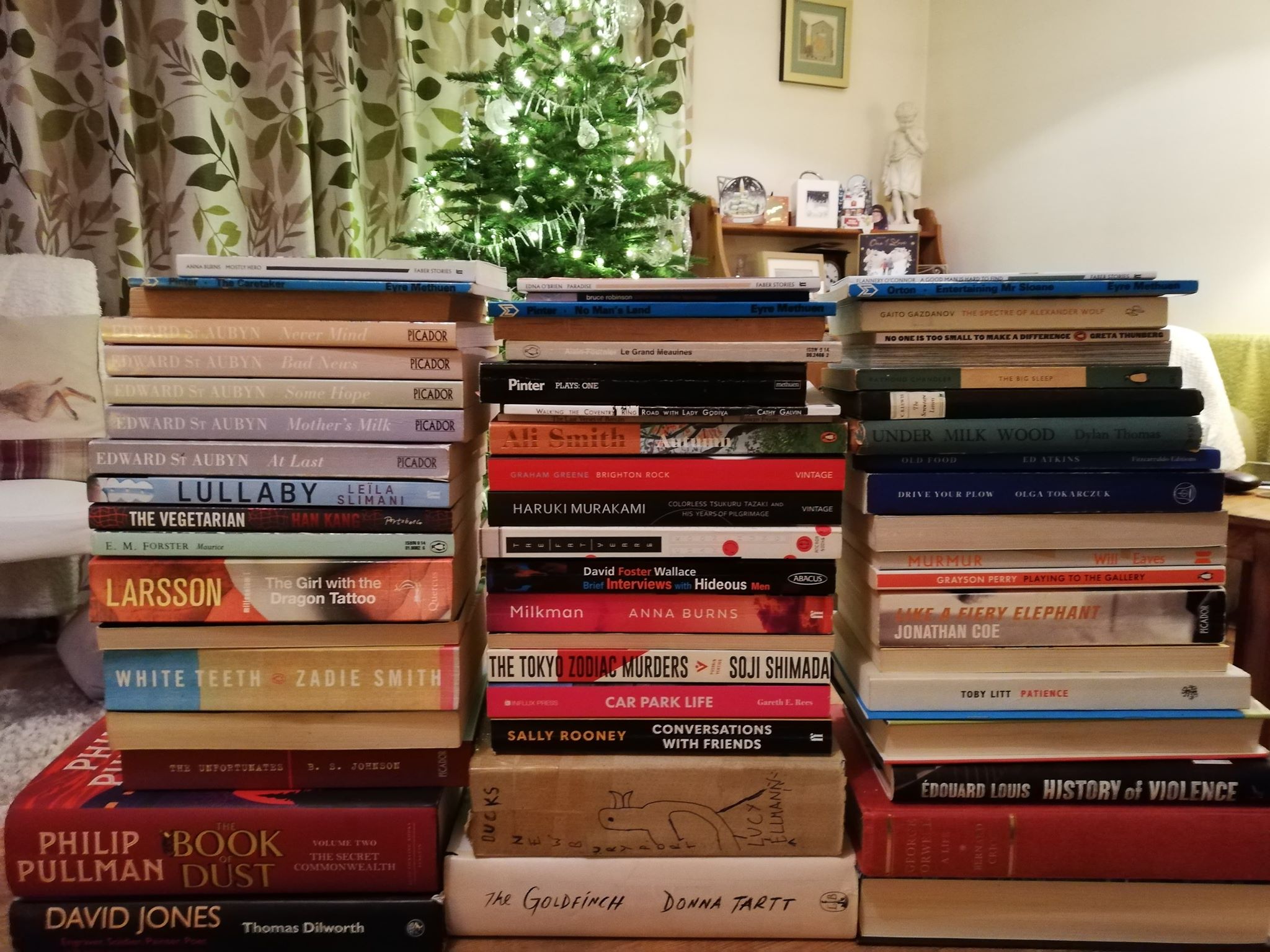

At the beginning of the lockdown, I managed to keep a good habit of reading for an hour or so in the morning in the time that had previously been my commute. Having a read in bed with a tea is much better than reading in the Tube crush, with one eye on getting a seat after Bank. By the summer, my attention span and my drive to work completely packed in. I managed a handful of articles for the blog but really I’ve neglected writing all year, and I’m a bit disappointed. I owe lots of people reviews and I’ve got a shamefully big backlog of Advance Reading Copies to get through. I have still enjoyed dozens of really funny, absorbing and fascinating books this year, and lots of my reading was in preparation for one article or another that I was either too lazy or too overwhelmed to write.

But I think we’ve all earned some slack. So instead, I’m going to view my reading in 2020 as a gigantic pre-reading to all the superb, Witty, Original and Viral (👉👈🥺) content that I’m going to do, I promise, in 2021. You have been warned. And really, I can’t sing the praises enough of the books below. They really have been the highlight of my year.

Books that I loved…and which really deserve reviews

I had a long list of debut titles and new releases that I was hyped to read this year, as well as loads of debuts from 2019 that I was late to the party for. An early favourite was Candace Carty-Williams’ funny, truthful Queenie, which lifted my spirits in January after a rubbish Christmas election. I loved the run-down, almost noir vibe of Elisa Shua Dupin’s Winter in Sokcho, a slim novel translated from French by Aneesa Abbas Higgins. It’s the story of an intelligent, overlooked French-Korean girl working at a guesthouse near the North Korean border in the middle of a bleak winter. An unexpected guest arrives, a French cartoonist determined to cross the border, and they strike up a sort-of-friendship that unfolds with a sly conclusion. The setting is cinematic and striking; I went through this one in two sittings.

Such a Fun Age, Kiley Reid’s sharp satire on race politics in America and the double-standards of liberalism, was entertaining and thought-provoking. It’s 2015 and Emira is a young black woman who works as a babysitter for Alix, a feminist blogger who’s looking forward to helping coordinate Hilary Clinton’s campaign. A white police officer accuses Emira of ‘kidnapping’ Alix’s daughter whilst grocery shopping. Footage of the incident goes viral, leading Alix to feel duty-bound to intervene and ‘help’ Emira in any way she can. But Emira is wary of this help, and Alix has her own reasons for wanting to make friends with a woman she really knows nothing about. I loved how Reid gets inside the heads of her characters, and exposes their prejudices, blind biases and their virtues; she’s also great at building tension, and some of the messy confrontations between Alix, Emira and their friends were priceless.

I finally got around to Girl, Woman, Other, too (another fresh take: Bernadine was totally robbed last year) which for me read like a marvellous state-of-the-nation novel. Although you should rightly shudder at the thought of something like a Brexit novel, Girl, Woman, Other takes on the questions of identity, politics and race that have defined the last few years (although Bernadine Evaristo and lots of other Black writers have been doing this for years anyway). On the day that Brexit has finally passed into law, and in the wake of a year that’s seen mass protests for racial equality, police violence on both sides of the Atlantic and a government that refuses to admit even that institutional racism exists, it’s important to read novels that feel properly, directly political.

One debut that really got in my head was Eliza Clarke’s Boy Parts. I had actually been anticipating Boy Parts for something like seven months before it was published by the inimitable Influx Press this summer, and, unlike basically everything else that you hype up for yourself for that long, Boy Parts was even better than I hoped it’d be. Irina is a 20-something artist in Newcastle who takes explicit photographs of average-looking men that she picks up, who are desperate to please her. She’s been offered a solo show at a gallery in London, just as she’s found a new model: the deliciously naive and gawky checkout boy from Tesco. Irina is really grim – which is hilarious, and following her nasty monologue as she schemes, manipulates and photographs her way around her friends and subjects is like riding a rollercoaster. If you have a strong stomach and a taste for sociopaths, Boy Parts is great fun and a brilliant inversion of the male gaze. I think I’m going to re-read it and write something in the new year. Much To Think About.

Speaking of strong stomachs, I was blown away by Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season, a story of black magic and ultraviolence in rural Mexico that unfolds with a hypnotic speed. One memorable tube journey I re-read an opening of a chapter over and over, thinking, how did she do that? In the village of La Matosa, the Witch is dead – her body found mutilated in an irrigation ditch at the height of a boiling, intolerable summer. Melchor writes in breathless paragraphs, with very few breaks or full stops, and as we move between people connected with the Witch and her murder we slowly learn what violence, cruelty and magic have led to her death. I think, objectively, there’s more twisted violence and terrible things in Hurricane Season than anything else I’ve ever read (Blood Meridian has been staring at me from the shelf for years). If you’re a fan of folk horror or True Detective, then get on this. All credit to Sophie Hughes for her excellent translation.

The final, most magical novel I wanted to write about this year was the slim Piranesi, the latest book by Susanna Clarke. At the moment I’m re-reading Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, which is an absolute favourite of mine, and Piranesi doesn’t disappoint: another weird, pretty tale of magic. The House is an endless labyrinth of vast, empty halls filled with thousands of crumbling statues and populated by birds, fish and bones. Piranesi has lived here alone forever, maybe, visited only by the mysterious Other, who wants to unlock and harness the power of the House. Is he a friend or a foe? A melancholy meditation on loneliness, with an abundance of Gothic Wonders. What’s not to love.

Non-fiction

As anyone who saw me before lockdown and my Twitter avi will attest, my January was consumed by Helena Atlee’s The Land Where Lemons Grow. I got this as the ultimate escapism and wholesome content from the wretched mess that was December 2019 and the prospect of another four years of listening to Boris Johnson; how naive I was. The Land Where Lemons came out in 2015: an expert on Italian gardens and culture, Atlee takes us on a surprisingly fascinating and richly interesting tour of Italy and the country’s rich appreciation and culinary heritage surrounding citrus fruits. A nice mix of history and culinary memoir, I especially liked reading about Sicily, where it’s the cold of the mountain air around Etna that makes the blood oranges so…orangey. The Land Where Lemons Grow also prompted me to make some shite gloopy marmalade, and proved my belief, from Umberto Eco, that every subject in the world is fascinating when looked at and written about in the right way.

Another book that fits that mould is Owen Hatherley’s Red Metropolis: Socialism and the Government of London. London – the home of the overpaid and out-of-touch metropolitan liberal elite – is far more complicated and neglected than the tabloids and rural Tories might have you think. In fact, despite the fact that it’s the heart of central government and home of some of the wealthiest people in the country, most Londoners suffer from some of the very worst wealth inequality and housing that a decade of austerity have inflicted upon the UK. Hatherley, an architectural critic and culture editor of Tribune, investigates London’s surprisingly left-wing history, from the decent council housing built by the Greater London Authority to the radical legacy of Red Ken, Boris Johnson’s typical uselessness and what Sadiq Kahn can do to put the city on the right tracks again. Since moving to London, I’ve worked hard to learn as much as I can about our capital and its contradictions, and Red Metropolis has ignited my interest in architecture, council housing, and municipal local socialism. With the Mayoral elections coming in May 2021, we can all do with a more nuanced understanding of our capital city, and the ways that we should govern the entire country better.

Another really important study of social welfare in Britain today that came out in 2020 was Feeding Britain, by Tim Lang, a former policy advisor and currently Professor of Food Studies at City University. The food system in the UK – what food we eat, where it comes from and how sustainably it’s sourced – is in perilously bad shape. We need to rethink how we feed ourselves and how we can make sure that food policy creates an equitable, truly fair society. As Marcus Rashford’s campaigns over the summer have shown, food is about so much more than hunger – it’s about opportunity, and fairness, and only a properly resilient and locally-driven food system will make sure that everyone in Britain eats and lives decently. I have no brain for figures or statistics, but Feeding Britain is replete with diagrams, tables and percentages, and Lang’s straight-speaking, plain prose does a fantastic job of explaining the knotty worlds of food supply and social change. If you want to understand the full impact of austerity and what we can do to make social life fairer and more decent, start with Feeding Britain.

For lighter reading, I can’t recommend more highly Tete-Michel Kpomassie’s An African in Greenland, which I reviewed back in June. A remarkable true tale, An African in Greenland is a young man’s story of how in the 1960s he ran away from his home in Togo, West Africa, and went to live among the Eskimo of Greenland, who welcomed him with open arms. It’s a surprisingly upbeat and innocent story, perfect as we won’t be travelling abroad anytime soon. I also only have good things to say about Brian Dillon’s Suppose A Sentence, from the same publisher as Hurricane Season, which is a series of essays investigating twenty-seven sentences: what makes them brilliant, and how grammar, language and syntax can elevate prose.

Journalism

I’ve been paying more attention this year to which journalists I’m reading and where I’m reading them. One of my favourite stories this year was Tom Lamont’s ‘The invisible city: how a homeless man built a life underground’, about a man who dug a bunker under Hampstead Heath. It totally grabbed my attention and didn’t let me go until I realised I’d lost a whole day I was supposed to be writing something. I religiously read The Guardian‘s Long Reads, but it was a few more months until I realised all my favourite long reads of the past few years – including ‘Speed kills: are police chases out of control?’, and the spellbinding ‘Dulwich Hamlet: the improbable tale of a tiny football club lost its home to developers – and then won it back’ – were all from Tom Lamont. Spend a day or two going through his backlog, you won’t regret it.

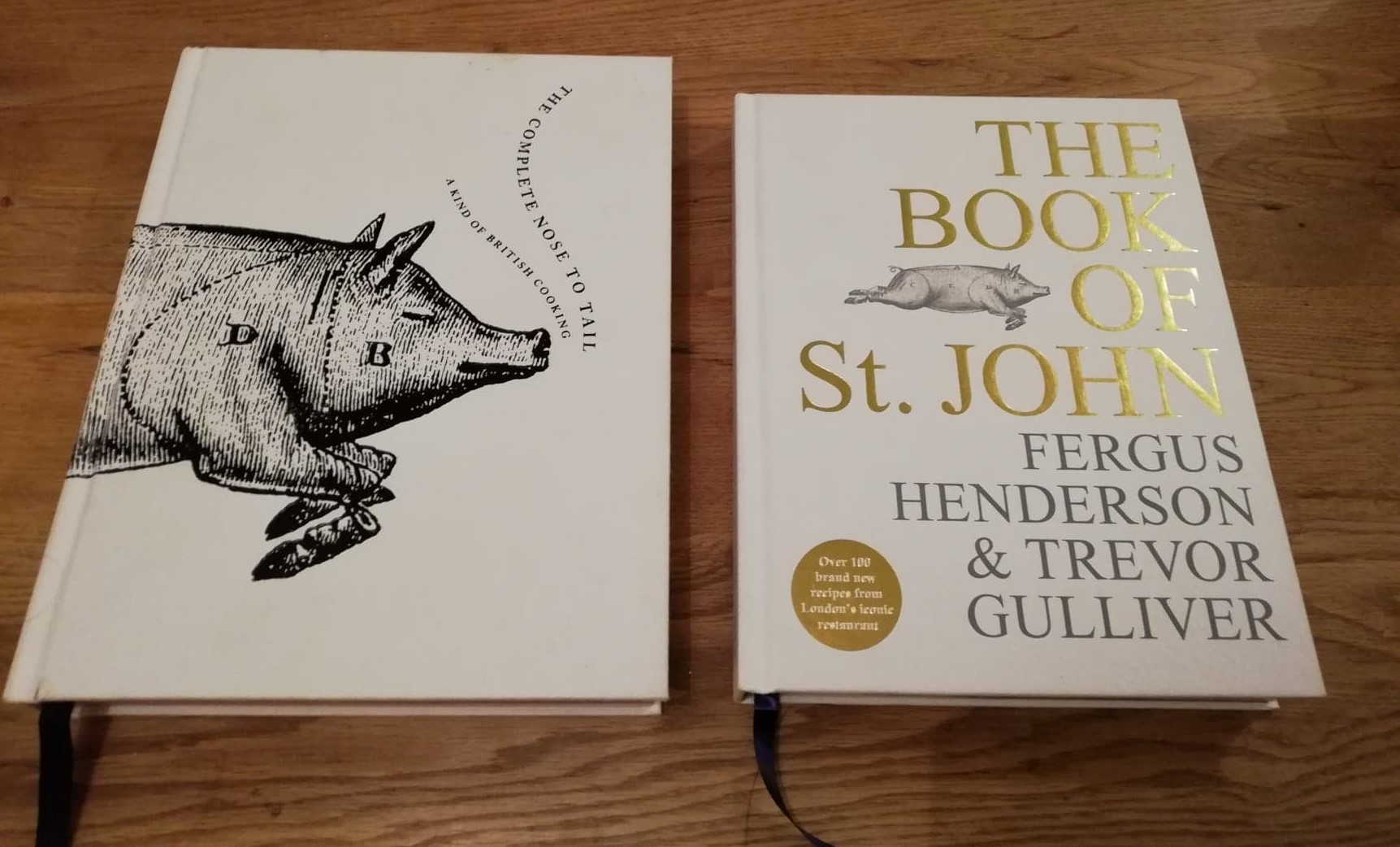

Food writing has occupied a lot of my time and reading this year, and Jonathan Nunn’s newsletter Vittles has been a firm friend throughout the year. Nunn, a food writer (who had the great twitter handle of @aadril), started Vittles back in March as a way of covering the anxious, terrible condition that the food world found itself in during the first lockdown – not to mention the troubles it still faces, many of which have been evident long before Covid. Written by chefs, critics and community leaders, you’ll always find something new and different in Vittles – from a guide to foraging in the city to an appreciation post of the UK’s regional chip shop vernacular. You can subscribe for very little, and support the future of good, open food writing.

The Crumbs of One Man’s Year

What is going to be hard about 2021 is that nothing about it is certain. During the first lockdown, you could console yourself with the knowledge that, eventually, the restrictions would be eased and life would start slowly going back to normal. But after the second lockdown, and Christmas being cancelled, and the likelihood of a third lockdown in the next fortnight or so, we don’t even have the security of an end in sight. It was going to last three weeks, then it was going to be over by Christmas, and now we’ll be lucky to go outside next April. Although no one can make the virus less contagious or deadly, there is absolutely no excuse for the way that the government has handled the crisis, and many hundreds of lives, not to mention jobs, businesses and social services, have been lost as a direct result of the current administration. For some reason, many millions of people in Britain refuse to hold the Conservatives responsible for anything they do, and that has to change. Honestly, we just love being miserable too much.

One more book that it’s nearly impossible to characterise: Etty Hillesum’s diary. I’m grateful to a Twitter mutual for making me aware of this book. Published by Persephone under the title An Interrupted Life, Etty was a young Jewish woman living in Amsterdam during the Second World War. She lived on the other side of the city to Anne Frank and had a very different life: a graduate student, she spent most of the first part of the occupation studying Russian, visiting friends and cycling around the canals. When the Nazis began introducing antisemitic laws, Etty bears each humiliation with courage and dignity, more than you can easily conceive. After a German soldier threatens her in the street, Etty is steely calm, channeling her fear into a commitment to bear witness to the horror around her:

I am not easily frightened. Not because I am brave, but because I know that I am dealing with human beings and that I must try as hard as I can to understand everything that anyone ever does…What needs eradicating is the evil in man, not man himself.

Etty’s courage was superhuman, and when the Nazis began rounding up Jewish people in preparation to deport them to the camps in the East, Etty volunteers as a go-between for other Jews who are less well educated and less able to get around the bureaucracy. She does what she can, from inside a camp, to make life more tolerable for her people. Of course that doesn’t save her. Although it sounds bleak, An Interrupted Life made a deep impression on me, and before the pandemic I managed to visit the house where Etty lived in Amsterdam. I don’t want to make a sham connection between what Etty went through and the experience I’ve had of the pandemic: all I can say is, in a year that has been full of frustrations, tragedy, fear and anger, I learnt a lot by reading and thinking about what Etty Hillesum wanted to tell us about her life.

Well there it is – lots of great novels, and fascinating non-fiction. Let’s hope for a better 2021 – it can’t be worse than 2020, right…? (please say right). Exciting, interesting stuff on the horizon.